* This post may contain affiliate links. Excess All Areas may receive

a small commission, at no cost to readers, if a purchase is made

What makes a perfume a classic? Michael Edwards dissects the divas of scent in a tome that has this week been named Fragrance Book of the Year…

Perfume is a world of molecules and metaphors, magic and mavericks. Its success is owed as much to a command of language as to science.

Briefs to perfume’s “noses” might looks like this: “a perfume that smells like fresh cherry wood licked by a green-hot oxygen fire in a Balinese temple” (from Tom Ford) … “a blossoming daffodil floating on an ocean of smoky Siberian snows (Marc Jacobs) ….or “a smell like the silks that have two colours in them, depending on the light” (Escada).

They might be much more generic: “Something extraordinary” (Frederic Malle’s Portrait of A Lady), or “If Coco Chanel were alive today, this is the perfume she would wear” (Chanel’s Coco Mademoiselle).

The “nose” answered a simple question: What would Coco wear? Photo: Allie Pollock

When former L’Artisan Perfumer creative director Pamela Roberts was commissioning for her Les Voyages Exotiques collection, she wanted “smells stolen by a travelling perfumer.”

To meet that brief, Bertrand Duchaufour sought inspiration in Africa to create the woody, spicy, smoky and animalic Timbuktu (2004), one of L’Artisan Parfumeur’s best sellers. He looked to the Malian “wusulan” ritual of scenting hair and skin with smoke, a potpourri of aromatic grass, spices, petals and pieces of wood soaked with fragrant oils, the recipe handed down by women through generations.

Australian fragrance connoisseur and cataloguer Michael Edwards loves the colourful back stories to the great perfumes of our time.

“We are in danger of losing this history,” he says. “Fragrance is the only art form that can be created and then bastardised – and nobody seems to complain. We are in danger of forgetting the legendary perfumes, or reinterpreting them as something we would like to believe they were.”

Timbuktu, woody, spicy, smoky, animalic, one of L’Artisan Parfumeur’s best-sellers. Photo: Trung Do Bao

Edwards, born in Malawi and educated in England, moved to Australia to live in 1983. Before Covid-19 he was dividing his time between Sydney, Paris and New York. His annual classification tome, Fragrances of the World*, has become an international resource, with a 30,000-strong database of fragrances. In 2017, his team of evaluators sniffed their way through 2,400 new concoctions, identifying the category and sub-categories each occupies on Edwards’s famous fragrance wheel.

His 1996 book Perfume Legends: French Feminine Fragrances, was a museum in a book. In it Edwards canvassed the classics, from Houbigant’s Fougère Royale in 1882 to Angel in 1992, his journey dating from the time scientists began to isolate and synthesise nature’s storehouse of scents – working out which chemicals could evoke cinnamon, bitter almonds, star anise, marzipan, vanilla, fresh hay…

Edwards drew on his extensive archive of interviews and discussions with the people behind 45 “legends”, from revered perfumers to company executives to bottle designers. They talked – forensically – about inspiration, compositions, and successes – some accidental – sharing history, science, lore, and the derring-do it takes to create an unforgettable scent.

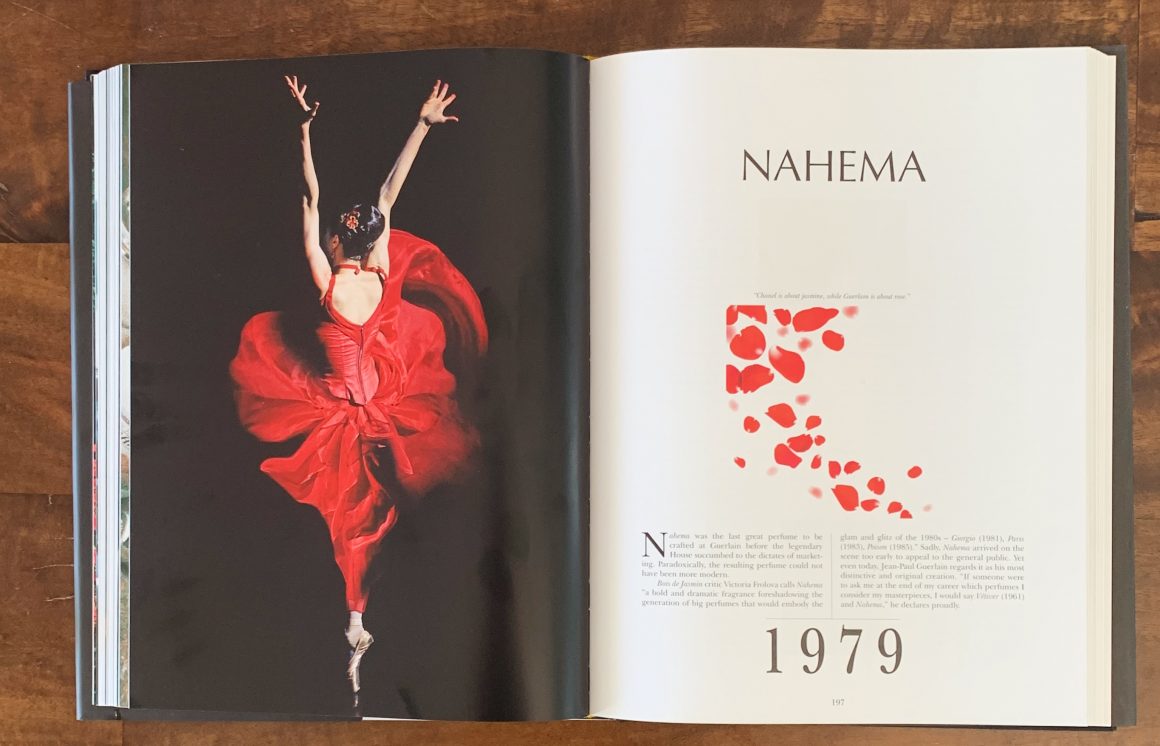

“Nahema is the most extraordinary fruity oriental rose. Imagine Bolero…”

For years, perfume lovers have clamoured for more, and finally late last year, the updated Perfume Legends II: French Feminine Fragrances* was published. This week, in a virtual ceremony, it won the 2020 Perfumed Plume Award Fragrance Book of the Year.

There are 54 perfume portraits in this version. New on the list are Féminité du Bois (Serge Lutens, 1992), Tocade (1994), J’Adore (Christian Dior, 1999), FlowerbyKenzo (2000), Coco Mademoiselle (Chanel, 2001), Timbuktu (L’Artisan Parfumeur, 2004) and Portrait of a Lady (Frédèric Malle, 2010).

The two that have been “rehabilitated” are Fracas * (Robert Piguet, 1948) and Nahema (Guerlain, 1979).

Their absence on the original list had been niggling away at Edwards. “Fracas was genius but when I wrote the original book it had been so transformed into plonk that I didn’t include it. Now it’s back to form, a celebration of Germaine Cellier, who was one of the great, great French perfumers.

“Fracas had everything. No matter what tuberose you are discussing it always comes back to Fracas. The accord is extreme, beautiful and continues to create a legend.

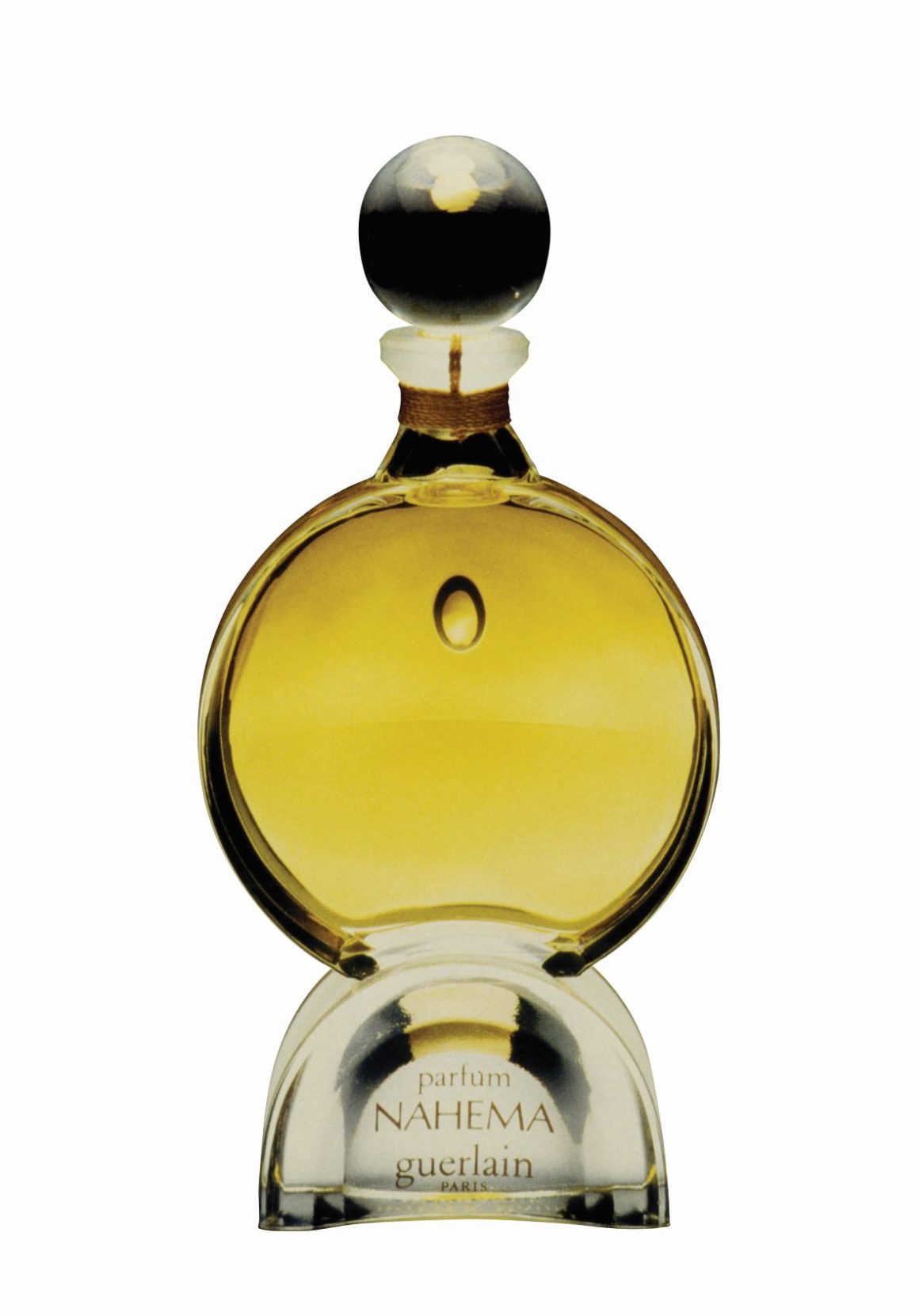

Guerlain’s 1979 masterpiece, Nahema, “rehabilitated” in Perfume Legends

“Secondly, Nahema. I loved it. But when I was working with Jean-Paul Guerlain on the first book, he got tired of talking to me! We had five inteviews and all he wanted to talk about was Samsara. Sadly he is no longer able to talk to us but the perfumer he worked with on Nahema – Anne-Marie Saget – did, so we now have the story it deserves.

“Nahema is the most extraordinary fruity oriental rose. Imagine Bolero. That slow hypnotic dance. Now imagine we transform the dancers into flowers – rose upon rose, dancing with a hypnotic fruit…”

It was a perfume, says Edwards, that pre-empted the glamorous heavy-hitters of the 1980s, like Giorgio, Paris and Poison.

In Legends, perfume critic Luca Turin is quoted in his inimitable style: “The first three minutes of Nahema are like an explosion played in reverse: a hundred disparate, torn shreds of fragrance propelled by a fierce, accelerating vortex to coalesce into a perfect form that you fancy would then walk toward you, smiling as if nothing happened.”

Robert Granai’s bottle “represents the alchemist’s search for the philosopher’s stone”

In arriving at his legends, Edwards had three criteria. They had to display “an accord so innovative that it inspired other compositions; an impact so profound that it shaped a new trend; and an appeal that is likely to transcend the whims of fashion.”

The perfumes that made the original list – among them Jicky, Mitsouko, Chanel No 5, Shalimar, Arpège, Miss Dior, First, Opium, Samsara – were, for their time, daring and, believe it or not, niche.

Many of them are no longer available in their original form, or can be sampled only at the Osmothèque, the world’s largest scent archive, in Versailles.

The perfume connoisseur’s archive of choice: The Osmothèque at Versailles

Back then, says Edwards over coffee in inner-Sydney’s Glebe, on a day fragrant with the promise of spring, perfumers were anonymous “people of the shade”, and perfumes were avant-garde creations designed for women with taste and money. “They were very limited. There was no such thing as eau de toilette at that time.

“With L’Air du Temps in 1948, perfume became more easy to understand, easier to wear. Look at Diorissimo, Madame Rochas, Calèche, Fidji … And later, Dune and Trésor – airier, more transparent. They don’t hit you over the head.”

“A good perfume must always be at once excessive and harmonious.”

Edwards confesses to being “totally addicted” to Paco Rabanne’s Calandre (1969). “Its fragrance sparkles … so subtle and fresh on the skin. To my mind, it remains as modern today as when it was created.

“And I admire Angel for its sheer innovation. Then look at L’Origan, Jicky … Confronting? Daring? So perfume should be!

Fragrance classifier, author and industry legend, Michael Edwards. Photo Gary Heery

“Every great perfume probably loses the market test. It affronts, and so they mark it down. Yet it’s that very quality, I am convinced, that makes it memorable. Give me a fragrance that 5% of people are totally addicted to and 70% loathe, and I’ll give you a $100 million grant!

“The reality is that broad appeal means you have to compromise: you end up with the best of the worst and the worst of the best.

“The average perfume is nice and pretty and forgettable. It’s hard to find one that has enough guts to keep you going.”

Dominique Ropion, who created Portrait of A Lady for Frédèric Malle, would concur. “A good perfume,” he says, “must always be at once excessive and harmonious.”

Serge Lutens is a modern-day genius, says Michael Edwards, and Féminité du Bois underrated

One of the most underrated perfumes on his list, Edwards believes, is Féminité du Bois (1992), which Serge Lutens created for Shiseido before launching his own brand. Its inspiration was the cedar of Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, and other borrowings from a Marrakech spice souk.

Serge Lutens * is a modern-day genius, believes Edwards. “He lives in a world so esoteric. He has been building a house in Marrakech for some 35 years. He still hasn’t finished. He writes every day for two to three hours to produce three to five words. His collaboration with Christopher Sheldrake has been quite remarkable.

“The impact of this perfume among perfumers was extreme. I could count a hundred fragrances that mined the inspiration of the Féminité Du Bois accord. That combination of wood warmed with the heat of fruit was extraordinary.”

Among subsequent interpretations were Dior Dolce Vita, Estée Lauder Sensuous, Jovoy L’Enfant Terrible, Comme des Garçons White and Giorgio Armani Sì.

But Edwards saves his true hero worship for Francois Coty, whose first fragrance was La Rose Jacqueminot in 1904. “Think of his genius! Prototype of a floral oriental (L’Origan 1905), prototype of a chypre (Chypre de Coty, 1917); prototype of a modern oriental, Emeraude (1921), four years before Shalimar.”

Francois Coty’s trailblazing Chypre de Coty, 1917

It was Coty who saw the benefit of a beautiful bottle, persuading René Lalique, who until that time had been a jeweller, to create flaçons that would be as seductive as the scents they contained.

Coty pioneered “gift with purchase”. He valued research. Each year he would come out with a new perfume for Christmas that he called Le Parfum Inconnu (The Unknown Perfume). If it worked in store it would emerge the following year with its proper name. Many women swore Le Parfum Inconnu was their favourite perfume, even though there were a dozen of them.

“He would never say that he was a perfumer,” says Edwards, “His business card said ‘fragrance designer’. He lost money on the stock exchange, played around with women, his wife divorced him, he died bankrupt in the 1930s.

“But with his death, he seeded the French perfume market with the perfumers, agents, financial directors, commercial directors, managers who had worked for him. They established new infrastructure, and created more legends.”

Perfume Legends II: French Feminine Fragrances is $215 from www.fragrancesoftheworld.com

This story was first published in Vogue Australia in August 2019.

* This post may contain affiliate links. Excess All Areas may receive

a small commission, at no cost to readers, if a purchase is made

'Classic perfumes | Legends in a bottle | Fragrance Book of the Year |' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!